At some point, every Linux admin has the same quiet realization: the server is stable until it isn’t.

Not because Linux is unreliable, but because everything around it is. Hardware ages. SSDs fail silently. Updates introduce regressions. Someone runs rm -rf in the wrong directory. And increasingly, ransomware and malware target Linux servers not because they are easy, but because they are valuable.

That’s why you need a solid backup strategy as a sysadmin or network engineer. Before you think about the most suitable tools for this, you should start with this important question:

What failures am I realistically trying to survive?

The answer leads to the classic 3-2-1 backup strategy. This article is not about abstract best practices. It’s about how I implement backup strategy for my servers. Perhaps you can learn a few things from my experience.

What's the 3-2-1 rule of backup?

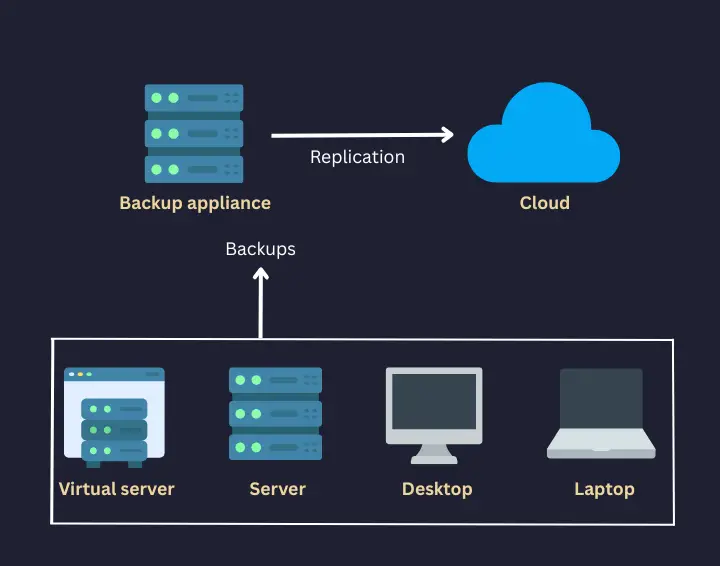

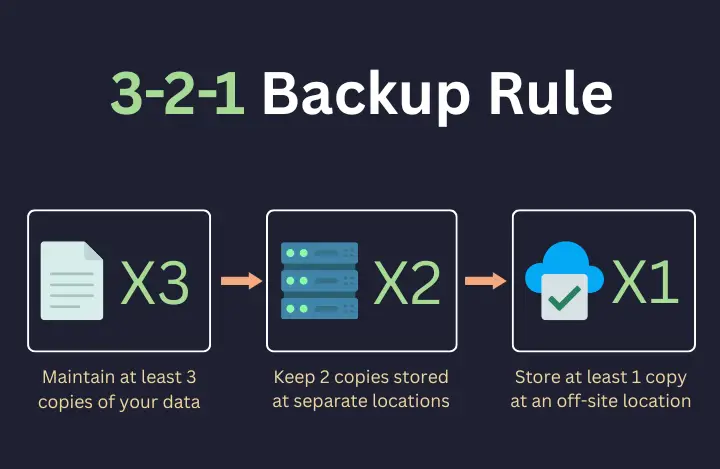

The 3-2-1 rule is decades old and that’s probably why it’s an unwritten industry standard. It says:

- Keep 3 copies of your data

- Store them on 2 different types of storage

- Ensure 1 copy is off-site

But the real value of 3-2-1 isn’t in the numbers. It’s the mindset: assume failure, design for recovery.

Here’s how I see each part of the rule in relation to real incidents I’ve seen (or lived through):

Principle |

What It Actually Protects You From |

3 copies |

Silent corruption, accidental deletion, bad updates |

2 storage types |

Disk/controller failure, filesystem bugs |

1 off-site |

Ransomware, theft, fire, total host loss |

Once you look at it this way, it will be easier to plan the backup strategy for your own servers.

First thing first: Decide what is worth saving

Before touching backup software, I did a full audit of my second production server.

Now, Linux makes it deceptively easy to back up everything. But backing up everything usually means backing up a lot of things that actively get in your way during restore.

I separated my system into rebuildable and irreplaceable parts.

Irreplaceable data (what I back up)

This is the data that represents time, decisions, and user actions. Some examples are:

- Application data directories

- Databases (exported as logical dumps, not raw files)

- /etc, service configs, system tuning, cron jobs

- Custom scripts and automation

- User-generated content (I don't wan to upset the devs)

Rebuildable data (what I don’t back up)

If the OS dies, I can reinstall it cleanly. I find it better to not resurrect a broken state from backup. Backups are for data, not technical debt in my opinion. Here's what I don't include in my backup:

- The operating system

- Installed packages

- Temporary files, caches, logs

Still, you can always create system snapshots or VM backups and have the entire server backed up. Most cloud server providers these days provide you easy ways to create automated as well as on-demand snapshots. If you have deployed servers on your own infrastructure in VMs, taking backup becomes easier.

This decision alone reduced backup size, complexity, and restore time.

Backup copy 1: Live production data (the fragile one)

Your running server is, by definition, the first copy of your data. But it’s also constantly changing, exposed to users and services, and the first thing attackers touch.

I treat the live system as ephemeral. Everything else in the backup strategy exists because I fully expect this copy to fail one day. That mental shift is important.

Backup copy 2: Local backup on separate storage

The second copy lives locally, but not on the same disk as the system. And this is where local backups shine. Local backups are what save you when:

- You delete the wrong directory,

- A config change breaks a service,

- Yesterday’s update turns out to be a bad idea.

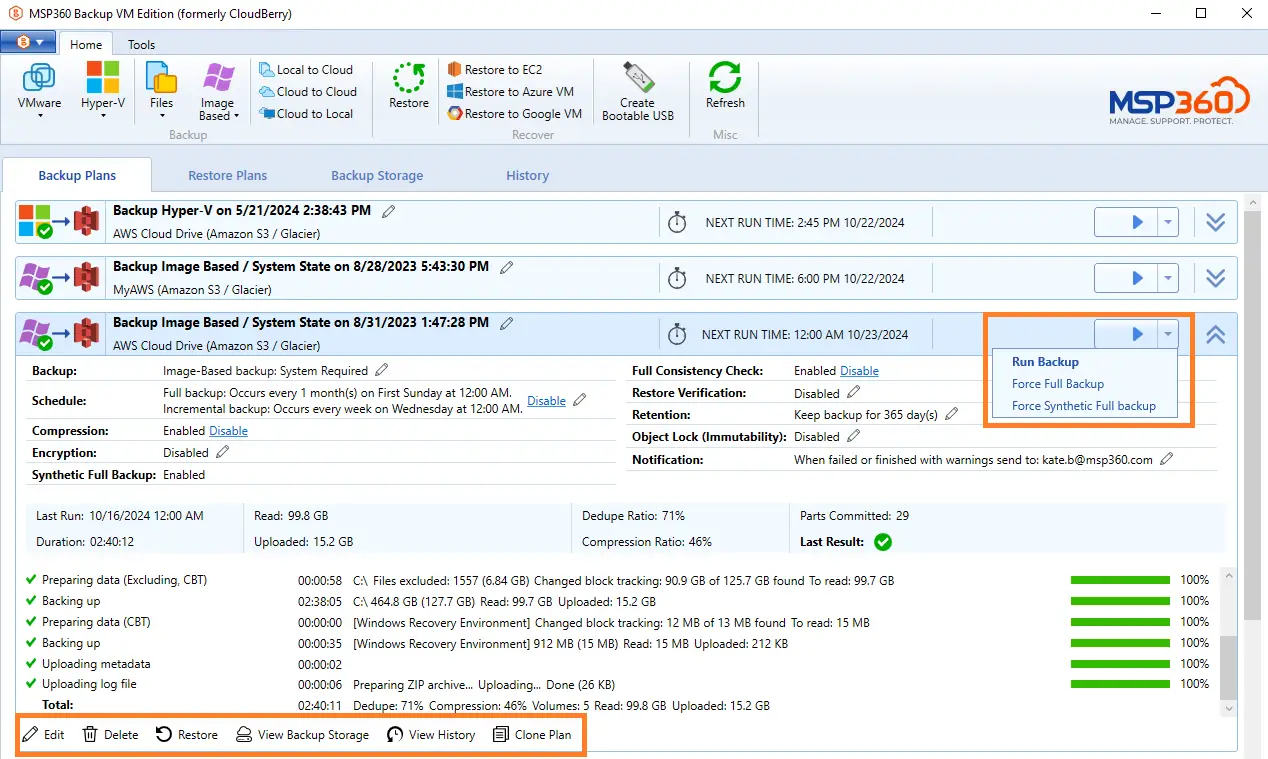

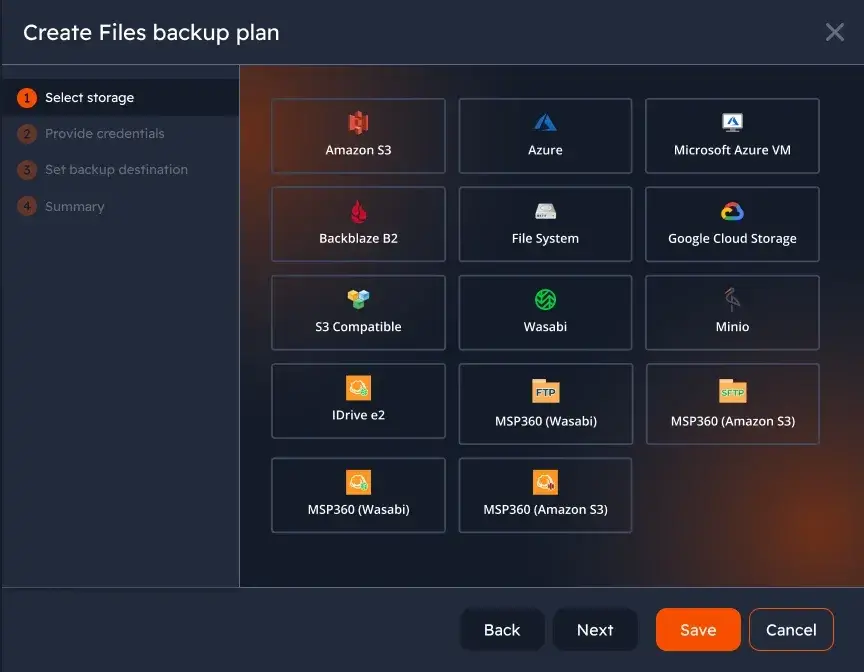

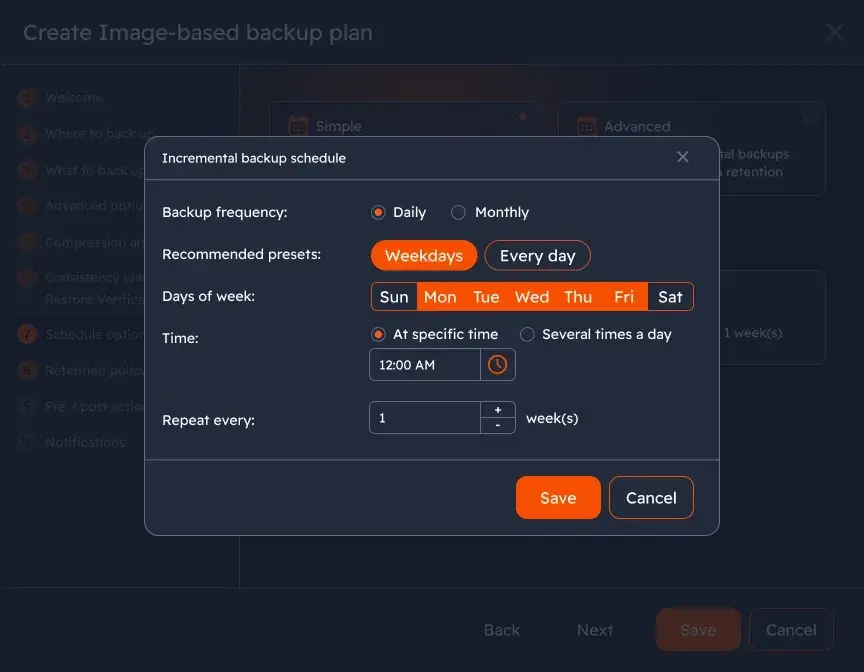

Using MSP360 Backup for Linux, I set up scheduled backups that run automatically and create incremental restore points. These backups sit on separate storage and give me the ability to roll back hours or days without touching the network or the cloud.

Local backups are often the fastest path to recovery. Still, local backups alone are not a backup strategy.

Backup copy 3: Off-Site backup to object Storage

The off-site copy is where the 3-2-1 strategy becomes non-negotiable. After all, you don't want to be in a situation where your server goes down taking the backup with it.

You may find the above meme funny, but the problem is very much real and you don't want to encounter such a scenario.

This is why a good backup strategy should include the option to create offsite backups.

If ransomware encrypts the server, local backups are usually encrypted too. If the machine is stolen or destroyed, everything local disappears.

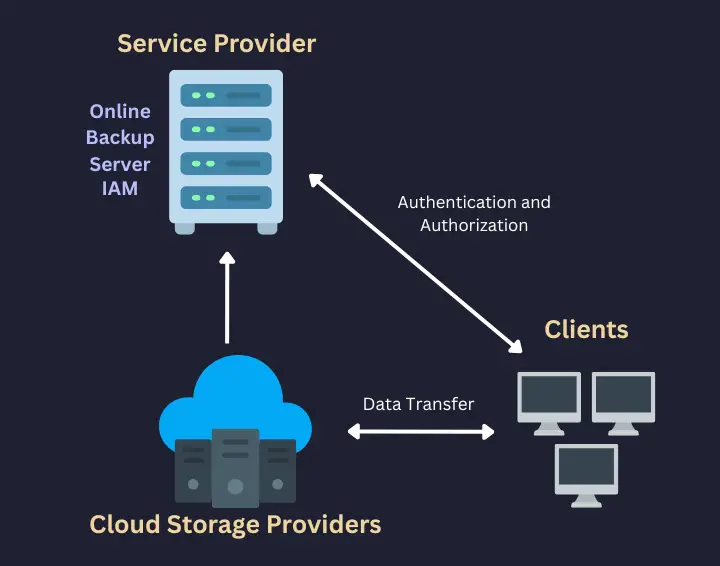

That’s why my third copy lives outside my infrastructure, in cloud object storage.

From Amazon S3 to Backblaze B2, there are a number of object storage providers. Similarly, there are plenty of CLI tools like s3cmd that allow you to deal with the remote object storage service.

Since I use MSP 360, I can skip the CLI and enjoy the comfort of GUI.

With MSP360, the same backup workflow that produces my local backups also encrypts and uploads data to S3-compatible storage. The data is encrypted before it leaves the server, stored with enforced retention policies, and verified after upload.

At this point, I can lose the server, the disks, the building it’s in, and still recover my data.

That’s the bar. Not that I would want any of this happen but I am prepared for the worst.

The “2” in 3-2-1: Why storage diversity matters

Many people misunderstand the “two storage types” requirement.

It doesn’t mean “two cloud providers” or “two brands.” It means two different failure domains.

In my setup:

- Local backups live on block storage.

- Off-site backups live in distributed object storage.

These systems fail differently, under different conditions, for different reasons.

A filesystem bug doesn’t affect object storage. A cloud outage doesn’t affect local recovery.

That separation is intentional.

Automation is not optional...not at all

The most dangerous backup strategy is one that relies on memory. If backups require human discipline, they will eventually stop happening. No matter how many reminders you put, you are likely to forget creating backups manually.

This is why everything in my setup is automated:

- schedules,

- retention,

- encryption,

- uploads,

- integrity checks,

- failure notifications.

MSP360 lets me define policies once and apply them consistently, without stitching together cron jobs and scripts. My rule is simple:

If a backup fails and I don’t know about it, I assume I have no backup.

Restore testing: The step everyone skips (and regrets)

⚠️ 1 backup == No Backup

✅️ 2 backups == 1 Backup

⛔️ Untested backups aren't backups

A backup you’ve never restored is not a backup. It’s a hope.

This is why you should periodically perform real restore tests:

- restoring individual files,

- restoring full directories,

- validating database dumps,

- checking permissions and ownership.

Most restore failures on Linux are not about missing data; they’re about context: paths, permissions, services expecting specific states. Testing reveals these problems early, when fixing them is not as stressful.

Conclusion

A solid 3-2-1 backup strategy is not about fear. It’s about honesty. Servers fail. People make mistakes. Software surprises you. By designing backups around layers, isolation, and recovery, you end up with a system that is predictable, boring, and dependable.

And in backups, boring is exactly what you want. You don't want the 'excitement' of data recovery.

As you can see, I use MSP360, formerly known as Cloudberry. What I appreciate about MSP360 in a Linux environment is that it doesn’t try to reinvent how Linux works. It doesn’t force proprietary storage, opaque formats, or all-or-nothing platforms.

Instead, it acts as a control layer orchestrating backups, handling encryption, managing retention, and letting me choose where my data lives.

That makes it a good fit for admins who want control without the usual chaos of assorted CLI tools.

If you run a Linux server today and rely on a single backup copy, this is your sign to rethink that choice. Just give it a try.